Problems have been described at the discrepancy between the current state and some desired future state. A problem-cause-solution pattern is common as a critical thinking approach providing argumentation supporting proposed solutions. This approach is particularly attractive if existing predictive models based on the causal actions are available. Based on new inputs to the model, existing predictive models provide a mathematical basis for calculating (predicted) new results within the limitations of the model. As a mathematical technique, predictive models have been successfully applied in a variety field from scientific endeavors to commercial activities like algorithmic stock trading, predicting accident risk for auto insurance, and healthcare outcomes.

When considering potential bias in problem solving, the predictive model is often a starting place. A good model is both as accurate as possible, and as simple as possible making it easy to understand and apply – and also easy to misapply if its limitations are not understood. Most models reduce the amount of control data because this simplifies the model enabling easier model development, validation and usage. Models are typically validated over a limited range of control variable values, but reality may not be constrained to that range. Complex systems in the real world are often affected by multiple control variables, and those may interact in interesting non-linear ways. The phenomenon being modelling is typically assumed to have a stable pattern of behavior, but this assumption is not always true. Humans, animals and artificial intelligence software can all exhibit learning behaviors that evolve over time. Predictive models of systems with learning behaviors developed at one point in time, may not be valid after new behaviors are learned. While model developers strive for prediction accuracy, most models are approximations. The degree of precision of an approximation may limit the predictive power of a model.

The tools we use alter our perception of the problems we solve – various paraphrased along the line of if one has a hammer, one tends to look for nails (quote investigator 2014). Even professionals with specialist expertise in particular fields tend to look problems from the perspective of their profession. Indeed, they may risk liability issues if they deviate from professional norms. The approach of identifying a cause may be seen as argumentative or evaluative, e.g., when there are multiple causes or explanations leading to a problem. The model development approach looks for variables that can be isolated and controlled, but these may not be the only causes of problems. In a legal (liability) context, there is a notion of a proximate cause being a cause that produces particular, foreseeable consequences. This typically requires the court to determine that the injury would have occurred, “but for” the negligent act or omission (the proximate cause). The widespread adoption of big data collection and artificial intelligence techniques (e.g., machine learning) has increased attention on the need to move beyond statistical correlation to prove causality. Recent progress in development of causality proofs (e.g. causality notations – (Pearl & Mackenzie 2018) has enabled significant improvements in development of predictive models. While the problem-cause-solution pattern is common, there are situations where action (or a solution) is required without establishment of a cause. The continuing operation of the system may not afford time for causal determination, or the costs on inaction may be too great. In this action bias context, the objective may be to make “reasonable” actions (e.g. to avoid known bad outcomes) rather than attempt to resolve the problem.

A desired future state may be described in objective terms; a desired state, however, must be desired by some real human (ie. it is subjective) as non- humans do not have desires. Broad consensus on some desired future state may provide some aura of objectivity. “Wicked problems” lie in the area where broad consensus of desired future state does not exist. If there is no consensus on the desired future state, then that lack of consensus likely applies not just to proposed solutions, or causality model selections, but also to the problem statement.

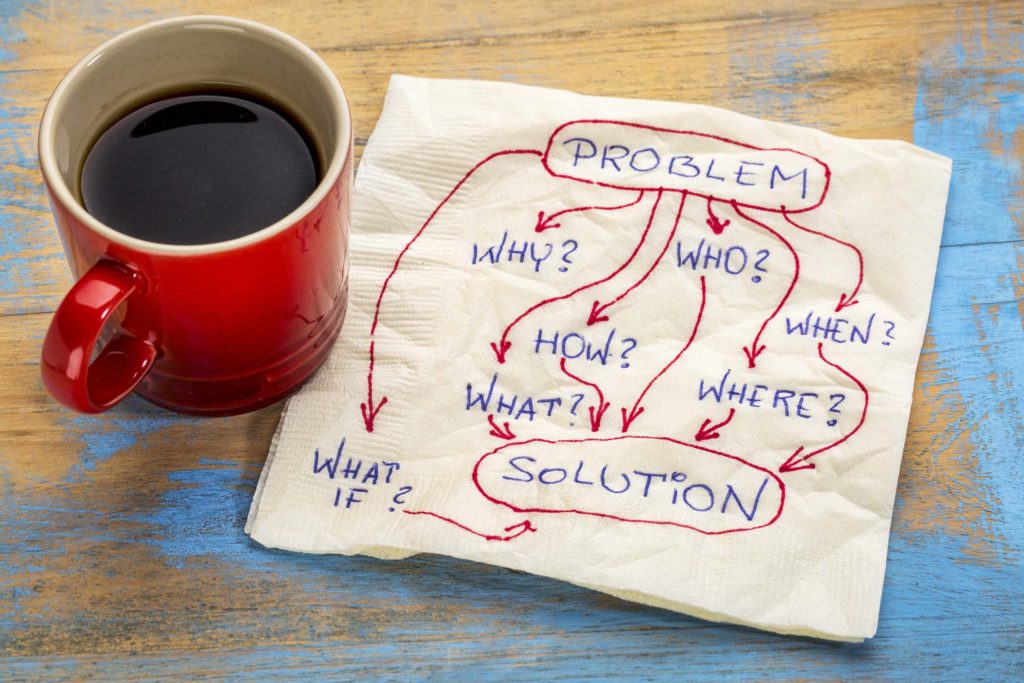

Problem statements delimit the scope of the problem to avoid extraneous matters and focus on the information relevant to the problem. The problem statement provides a context and forms a perspective on the problem. Perspectives include not just data observations, but also some meaning associated with those observations, focusing attention on the most relevant/ important observations. Framing the problem from different perspectives may result in different solutions, e.g., different problem statement will likely have different causal explanations proposed, leading to different solution proposals.There is often a rush to solving a problem rather than clarifying the problem statement first. A problem statement should provide clarity around the four W’s of the problem:

- Who – Who does the problem affect? Do they recognize it as a problem? Has anyone else validated that the problem is real? Who realizes the value if the problem is solved? Who else might have a useful perspective on the problem?

- What – What is the nature of the problem? What attempts have been made to resolve the problem?

- When – When does the problem happen? What are the antecedent and contemporary event? What is the Temporal Perspective?

- Where – Where does this problem arise? Is there observational data of the problem context correlated with its occurrence? What is the Geographic Perspective on the problem?

When it comes to your problem – what type of problem solver are you? Ad hoc or intuitive problem solvers risk spending their effort solving the wrong problem and not achieving the impact they might hope for. A systematic approach to capturing the problem statement and then reframing it from multiple perspectives may take more time initially to develop the problem statement, but avoids the risk of solving the wrong problem. Why is the problem worth solving? Why are you trying to solve it? Once you have your client’s problem statement, you can then refine it to focus on the problems that matter for greater impact.

When developing the problem statement for your client, understanding diverse perspectives can impact the scope of the desired future state as well as constraints on viable solutions. If you are developing client problem statements, you might be interested in our free Guide to Writing Problem Statements.

A course on the use of perspective to refine problem statements is now available.

If you need help with your problem statement contact me.

References

(quote investigator 2014) https://quoteinvestigator.com/2014/05/08/hammer-nail/

( Pearl & Mackenzie 2018) Pearl, J., & Mackenzie, D. (2018). The book of why: the new science of cause and effect. Basic Books.